Chinese

pioneers of Ventura

County subjects of new

museum exhibit

From China

to Ventura

For pictures and more information see

Photo

by Museum of Ventura County, Contributed photo

These men

from a Chinese fire brigade are shown in a parade in this photo taken in the

late 1800s by John Calvin Brewster, a chronicler of late 19th century and early

20th century life in Ventura

County. The Chinatowns in

Ventura and Oxnard both established their own fire

brigades, and some said it was because of slow response times from local fire

departments to blazes in those areas.

Chinese exhibit

What: The exhibit "Hidden Voices: The Chinese of Ventura

County" opens Saturday and runs through Nov. 25 at the Museum of Ventura

County, 100 E. Main St.

in Ventura.

Admission is $4 for adults, $3 for seniors and $1 for kids 6 to 17. Kids under

6 and museum members get in free. Admission also is free for all on the first

Sunday of every month. General museum hours are 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays

through Sundays. For more information, call 653-0323 or visit http://www.venturamuseum.org.

Festival: In lieu of an opening night reception, the museum will

host a Chinese Cultural Heritage Festival on Sept. 8 from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m.

Highlights of that will include a Chinese lion dance; a dance troupe and

calligraphy and brush painting shows from the Ventura County Chinese American

Association; and a papermaking demonstration from the Conejo Chinese Cultural

Association. Admission is $5; children under 12 and museum members get in free.

Other exhibit-related

events and dates at the museum include:

Oct. 7: A 2 p.m. screening of the documentary film "Courage

& Contribution: The Chinese in Ventura

County." The film

deals with 19th century Chinese immigration to California

and the evolution of Chinatown communities in Ventura

and Oxnard. It

highlights contributions of Chinese agricultural workers and merchants, Chinese

fire companies and the story of Bill Soo Hoo of Oxnard,

the first Chinese mayor elected in California

history. Free.

Oct. 27: A 1 p.m. book talk by William Gow, co-author (with Linda

Bentz) of "Hidden Lives: A Century of Chinese American History in Ventura County." Gow is the great-grandson

of Wong Ah Gow and Lou Oy Gow, who owned Gow Markets in Oxnard in the early 1900s. He will talk about

the role of Chinese immigrants in the evolution of Ventura County.

$5.

Nov. 18: A 2 p.m. lecture from local artist BiJian Fan on the

history of paper and various paper arts in China. He will also talk about

modern techniques and materials he uses in his kinetic sculptures. $5.

People interested in the

Cultural Heritage Festival and the other events are asked to RSVP at 653-0323

ext. 7.

The Chinatowns that

sprang up in Ventura and Oxnard in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries held together a tiny and hardscrabble community of gritty people who

had left their homeland to escape hardships only to find a new slate of them

here.

Almost all these people

came from the Guangdong (formerly Canton) province of southeast China, an area wracked by

rebellions and opium wars, as well as widespread hunger, poverty and death. In Ventura County

and elsewhere in the U.S.,

they suffered racial discrimination and were subjects of exclusion laws — the

first immigrant group ever targeted that way in U.S. history — that made it

impossible for most to bring their families here.

They eked out a largely

mundane life. Many — alone, not speaking English nor understanding our culture

— got jobs as farm laborers, ranch cooks, construction workers, fishermen,

domestic servants and laundry cleaners. In the local Chinatowns,

they lived in crude wooden buildings in tight quarters.

"It must have been a

really tough existence," said historian Linda Bentz of the Ventura County

Chinese American Historical Society, who wrote a 47-page journal last year

about the early Chinese here. Then, almost as quickly as they emerged, the

local Chinatowns faded away, vanished in the

annals of time. They were a secretive people and left behind little in the way

of records, diaries, keepsakes or photos.

But bit by bit, a clearer

though still fragmented picture of these local Chinese pioneers is emerging —

cobbled together from a historical olio that includes ceramic shards excavated

in present-day downtown Ventura, a few family heirlooms still floating around

here and there, the discovery of Chinese fish camps at the Channel Islands, and

traces and hints in rare old interviews and newspaper articles.

Much of this, and Bentz's

journal work, is included in the new exhibit "Hidden Voices: The Chinese

of Ventura County" that opens Saturday and continues through Nov. 25 at

the Museum of Ventura County in Ventura.

Bentz's work, which took

10 years to complete, was published last year under the museum's auspices in

the Journal of Ventura County History.

It was a reminder to the

staff "that we hadn't featured that part of our local history in a long

time," said the museum's Ariane Karakalos, who co-curated the exhibit with

Bentz.

"A lot of people

will be surprised that the city (as well as Oxnard)

had a Chinatown," Karakalos said. "A

lot of people aren't aware of that piece of local history."

It is "super

interesting," she added, "to see how these people came here and were

so very different."

A

THUMBNAIL TOUR

The

museum sports pieces of these people and their culture. A case will house what

Bentz called "brownware" — fragments of ceramic soy sauce jars,

dishes and the like, along with old coins.

"It

has a lot of meaning, realizing that someone used these things 150 years

ago," Karakalos noted.

Bentz

dug up a circa 1900 goods inventory from a Ventura Chinatown store as part of a

display on the importance role merchants played in those days. Among its items:

rice, brown sugar, pork, dried fish, vegetables, flour, black tea, cigars and

herbal medicines.

One

centerpiece figures to be the 1910 wedding dress of Nellie Yee Chung, who was

born in Ventura in 1888 and was an early

resident of its Chinatown.

The

hand-embroidered silk gown, adorned with decorative flowers and birds and

featuring a mix of pink, purple, green and charcoal black colors, is the thing

that will draw eyeballs in the exhibit room, Bentz predicted.

"It's

fantastic," she said. "It's the original thing. It's just

gorgeous."

The

dress is on loan from family descendants, Karakalos said, adding, "It's a

rare find."

Also

part of the exhibit is an abacus — Chinese shopkeepers didn't have cash

registers then. This one has wooden counting balls fashioned to resemble

pearls, Karakalos said.

Another

unique item on view is a Chinese queue, a plait or ribbon of hair worn hanging

from the back of the head. Most Chinese men, the curators noted, cut their

queues after 1911 in the dying days of the old dynasties and the coming of the

Republic of China.

More

cultural flavor will come from a contemporary lion costume on loan from Irene

Sy, the principal of a Chinese language school in Camarillo and vice president of the Ventura

County Chinese American Association.

The

costume, Sy explained, is used when people perform the lion dance at events

such as weddings, the opening of a business and, of course, the biggest celebration,

the Chinese New Year.

The

lion, she said, is an auspicious animal in Chinese culture and its meaning is

to bring peace, happiness and prosperity to the community.

Both

her group and a companion organization, the Conejo Chinese Cultural Association,

are part of the museum exhibit and also will participate in a Sept. 8 Chinese

Cultural Heritage Festival there.

The

exhibit is an opportunity to "share our culture and our history" with

the community, Sy said.

"It's

very impressive, and it's important to recognize the minorities of Ventura County

and the contributions of immigrants to our society through history," said

Yingchun Wu, a Newbury

Park resident and

president of the Conejo Chinese group.

ROUGH

DAYS

The

late 1840s Gold Rush brought many thousands of Chinese to California,

which they called Gum Saan, translated as "Gold Mountain."

Chinese miners were robbed, driven from claims and subject to an 1852 foreign

miners' tax that eventually was imposed only on them, Bentz wrote in her 2011

journal.

Around

the mid-19th century, the Chinese also came to Ventura. The Chinatown there initially was

along Figueroa Street

between Main and Santa Clara

streets.

As in

California

and the nation, the Chinese presence drew opposition. In 1882, Congress passed

the Chinese Exclusion Act that barred Chinese laborers from entering the United States.

Ultimately, the law was extended all the way into the 1940s.

Elsewhere,

the first wave of Chinese Americans were hanged and banished; there were

lynchings in Los Angeles, and Chinatowns across the West were burned to the

ground, according to Jean Pfaelzer's 2007 book "Driven Out: The Forgotten

War Against Chinese Americans."

Ventura County largely avoided such

large-scales skirmishes and tragedies, Bentz said.

But a

countywide Anti-Chinese League did form, and held weekly protest meetings at a

local hall. They thought the Chinese were "filthy" and at one point

tried to establish an American laundry because they didn't like the Chinese

doing that work, Bentz noted.

Local

papers joined the chorus. The Ventura Free Press, an ancestor of this paper,

stated in its Feb. 26, 1886 issue that "We are nothing these days if not

anti-Chinese." Another article on April 2 that year began bluntly:

"The Chinese must go."

But

things here generally didn't turn violent, though an 1893 protest march through

the Chinatown on Figueroa Street reportedly was scary

enough that the Chinese thought they were going to be deported; they scattered

into their homes, barred the doors and turned off lights.

In

another incident, an early local merchant named Ung Hing had to drive away a

mob beating on his door by threatening to shoot them with a pistol. But that,

Bentz said, "was about as rough as it got."

Through

all this, the local Chinese persevered. By the 1890s, Bentz wrote in the

journal, Figueroa Street

"was filled with the sights and sounds of a bustling ethnic

community." The Chinatown population was

thought to be around 200.

There,

one could find mercantile businesses, employment firms, a barbershop,

residences, a kitchen and other buildings. Nellie Yee Chung, in a later

interview, described simple two-room houses in Chinatown

that were connected in the back. Residents there raised chickens and pigeons,

and some gardened. They built a shed to dry clothes.

After

land around the San Buenaventura Mission was sold and developed in 1905, the

Chinese were driven from their homes. They relocated to a second Chinatown on the north side of Main Street from west of the mission to Ventura Avenue that

lasted until about 1920.

OTHER

PURSUITS

Oxnard's Chinatown rose almost as

quickly as did the town, which incorporated as a city in 1903, a mere five

years after a sugar beet factory was built there by the four brothers for whom

the city would be named. Many Chinese laborers moved to Oxnard to work in the beet fields.

An

1899 article in the Oxnard Courier noted that the area did not have a Chinatown

as in Ventura and Los Angeles — but such an ethnic enclave soon

took hold.

Oxnard's Chinatown initially was

located on Saviers Road

(now Oxnard Boulevard)

between Fifth and Sixth streets, and later shifted to Saviers between Seventh

and Eighth streets, bounded by A

Street.

Like

the Ventura version, the Oxnard

one had a China alley

through the middle and its own fire brigade; some said the latter were

established after slow response times from existing local departments to blazes

in the Chinatowns.

They

were also home to shadier activities. Both local Chinatowns had gambling halls

and opium establishments, and the Oxnard

one also had a saloon and "houses of ill repute." In the journal,

Bentz related an incident where Bartley Soo Hoo, of Oxnard's famed Soo Hoo

family, roller-skated in front of one of the brothels once during his childhood

and was admonished by one of the madams to keep quiet as "my girls are

asleep."

In a

way, that type of behavior was understandable, Bentz said. Many of the Chinese

were far away from home living in a hostile society that disliked them and

tried to pass laws against them. So they turned to such things.

"And

maybe sometimes they needed to smoke a little opium to make them feel better —

kind of like happy hour now," she said.

Both

local Chinatowns also were home to the Bing

Kong tong, Bentz wrote. Tongs were fraternal groups in the tight-knit Chinatowns everywhere. Some were benevolent, helping

people there find housing and jobs, but others were involved in protection

rackets and criminal activities; the Bing Kong tong was suspected of the

latter.

"We

don't have any evidence it was happening in these communities (Ventura

and Oxnard),

but that's what they were known for," Bentz said.

MOVING

ON

The

exhibit touches on the five people profiled in Bentz's journal. In addition to

Nellie Yee Chung, they include early Ventura Chinatown residents Minnie Soo Hoo

and merchant Tom Lim Yan.

Yan's

wide influence there lasted more than 30 years. In 1881, the Ventura Signal

dubbed him the "Boss Chinaman."

Merchants

tended to wield power in Chinatowns because

they were often the most educated and financially well off people there. They

often spoke English and assisted others with language translations, writing

letters and getting them sent home.

Thus,

their stores were gathering places and "a central element in the

community," Karakalos said. "They were pretty much the anchors of the

social fabric."

Merchants

also were exempt from exclusion laws, meaning they could travel to China and

return with family members.

The

exhibit also touches on latter-day local Chinese residents such as Walton Jue,

whose Jue's Market was a Main Street mainstay in Ventura for years until the

family gave it up recently, and Bill Soo Hoo, who was elected mayor of Oxnard

in 1966, thus becoming the first mayor of Chinese descent in California

history.

Soo

Hoo's run for City Council and to make changes in Oxnard reportedly came after he bought a lot

on Deodar Street

but was told he couldn't live there, that it was for "Caucasians

only." The exhibit is to include one of Soo Hoo's gavels from a council

meeting.

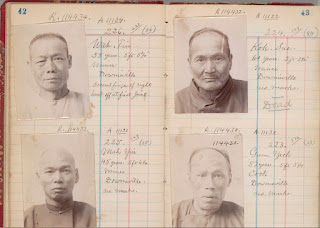

The

exhibit is augmented by photographs. Many of the early Chinese here are the

work of John Calvin Brewster, a chronicler of life in Ventura

County from his arrival in Ventura in the mid-1870s

to his death in 1909.

Bentz's

work is hardly done. She co-authored a book with William Gow titled

"Hidden Lives: A Century of Chinese American History in Ventura County"

that they hope to have out during the exhibit's run.

She

also just returned from Santa Rosa Island,

where she saw evidence of 14 Chinese camps where the men would spend three

months at a time harvesting abalone and the like.

MODERN

TIMES

Today,

the Chinese population in Ventura

County has shifted to the

east. Census numbers cited by Bentz show almost 10,400 people of Chinese

descent living in the county, up considerably from both the 2000 and 1990

censuses.

The

biggest concentration of them, some several thousand, is in Thousand

Oaks and the Conejo

Valley, Wu said. Only a

few thousand live "below the grade," Sy noted.

The

Chinese today are more likely to be doctors and health care professionals than

laborers. They are attracted by employers such as Amgen and Baxter Healthcare

Corp., Wu said. She'd know; she's a product quality coordinator at Baxter.

The

Chinese school in Thousand Oaks,

Wu added, now has an enrollment of 650; some 30 years ago, she said, they

started with 15.

Today's

Chinese community leaders say they are grateful for and indebted to the early

pioneers who came here and endured hardships.

Or as

Bentz said: "They were an amazing people."