Chinese American WWII Vets Remember Flying Tigers Days

Posted: 10/03/11 01:30 PM ET

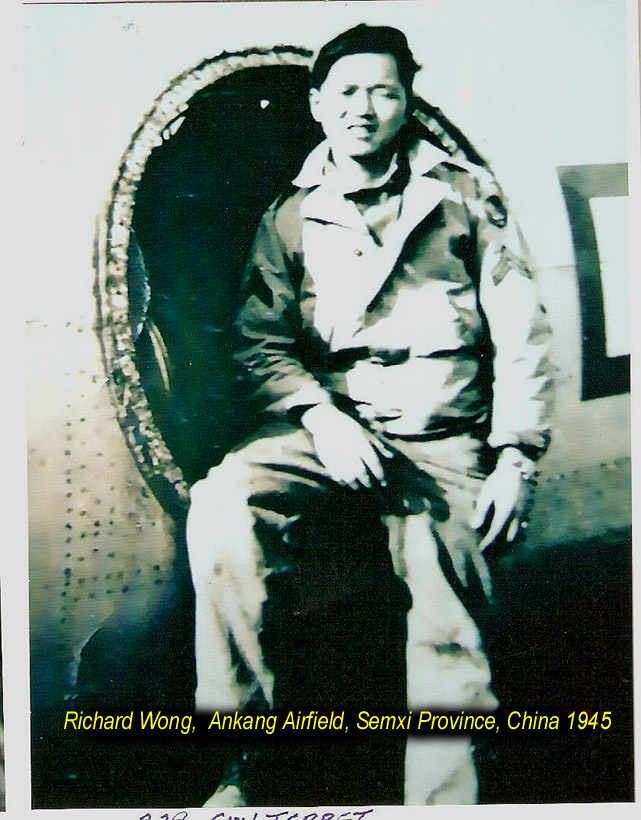

B-29 Gun Turret

Courtesy Richard Y. Wong

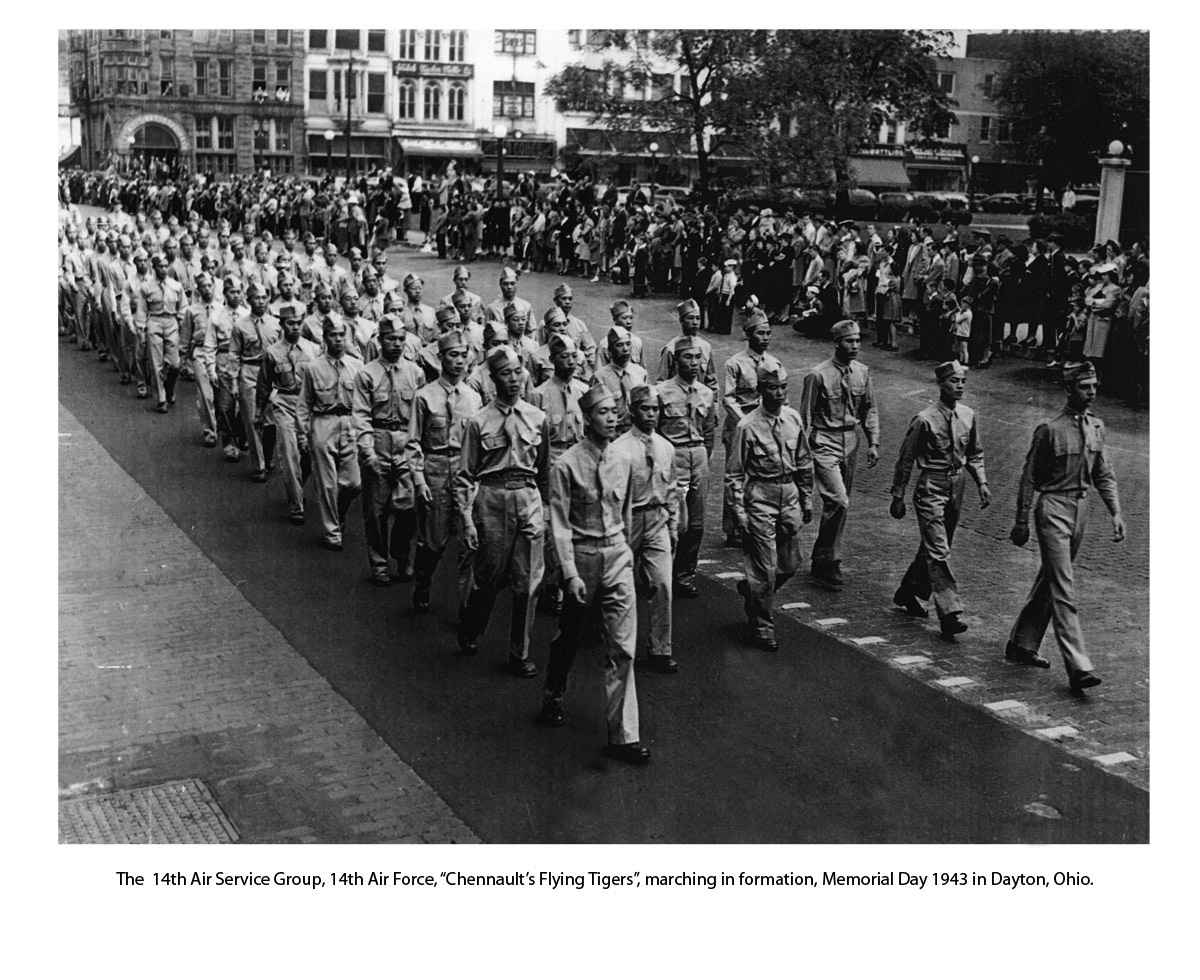

Now ranging from 86 to 93 years in age, these veterans came from across the country to bond and reflect. At the American Legion Kimlau Post 1291 in Chinatown, the first Chinese-American American Legion Post established after the war, they met friends and traded stories. A panel shared their experiences to a capacity crowd at the Museum of Chinese in America, where a short film featured photos of the men handsomely donning their American G.I. uniforms. They reminisced on the 1940s, when their uniforms first brought to them a sense of equality and pride. World War II marked many milestones for Chinese Americans. Most significantly, defense and other mainstream jobs became available, freeing Chinese Americans who had been confined solely to restaurants and laundries. The Montgomery G.I. Bill helped them afford education. Chinatowns transformed from bachelor communities to family communities, with the help of a special War Brides Act passed by Congress that enabled Chinese Americans to legally bring their brides over from China. Any soldier who served a minimum of 90 days gained citizenship, even if he had entered the country illegally.

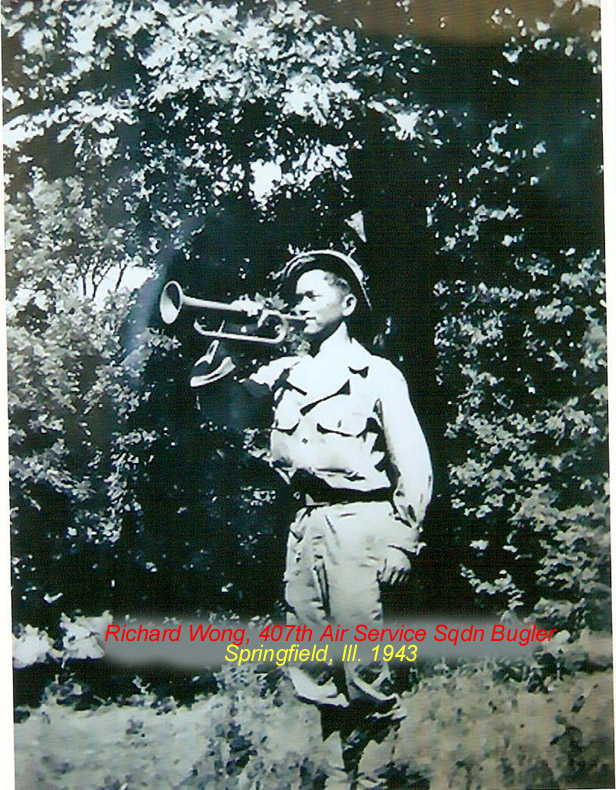

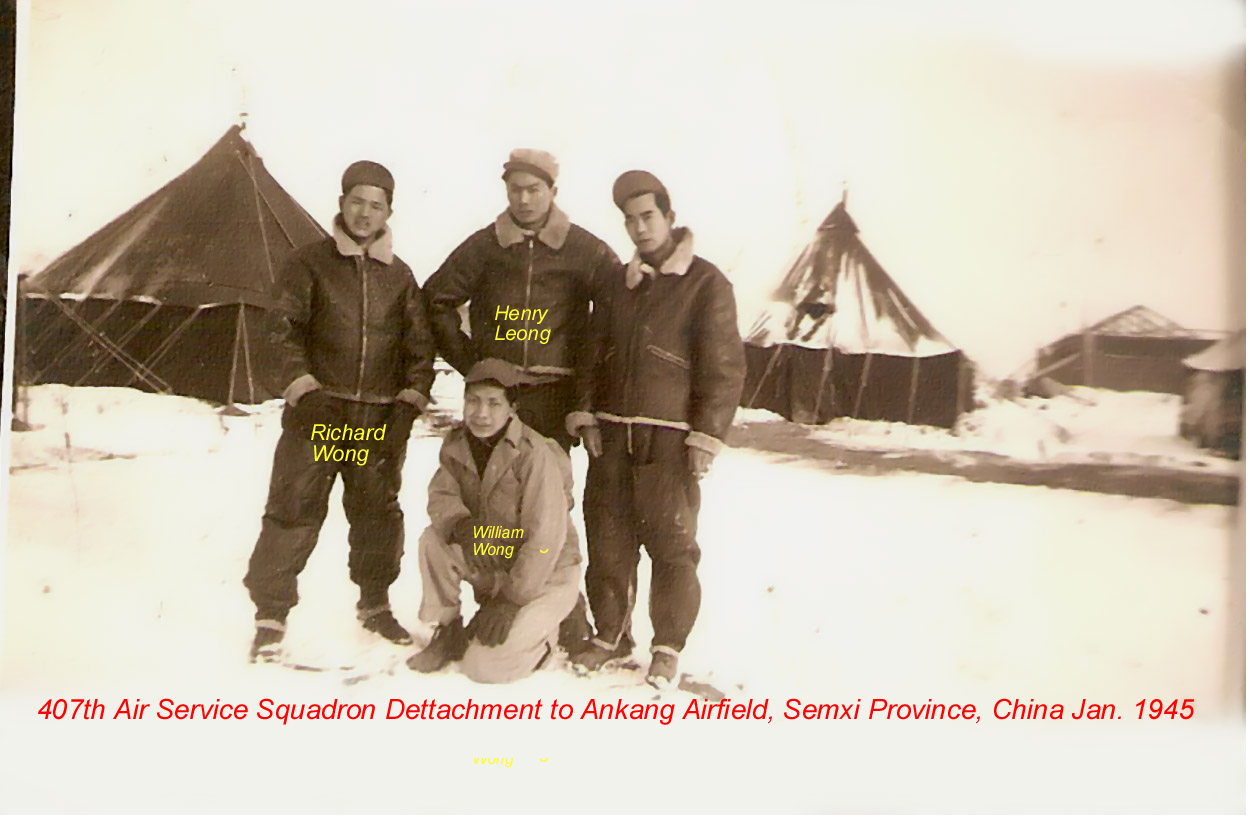

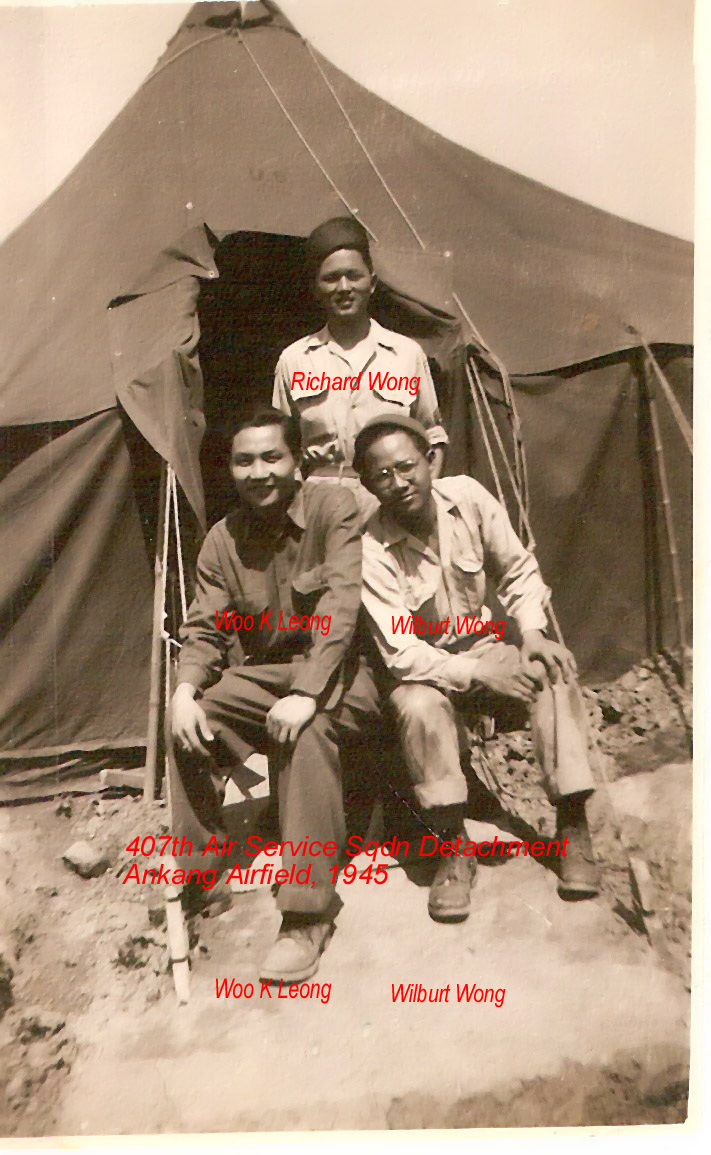

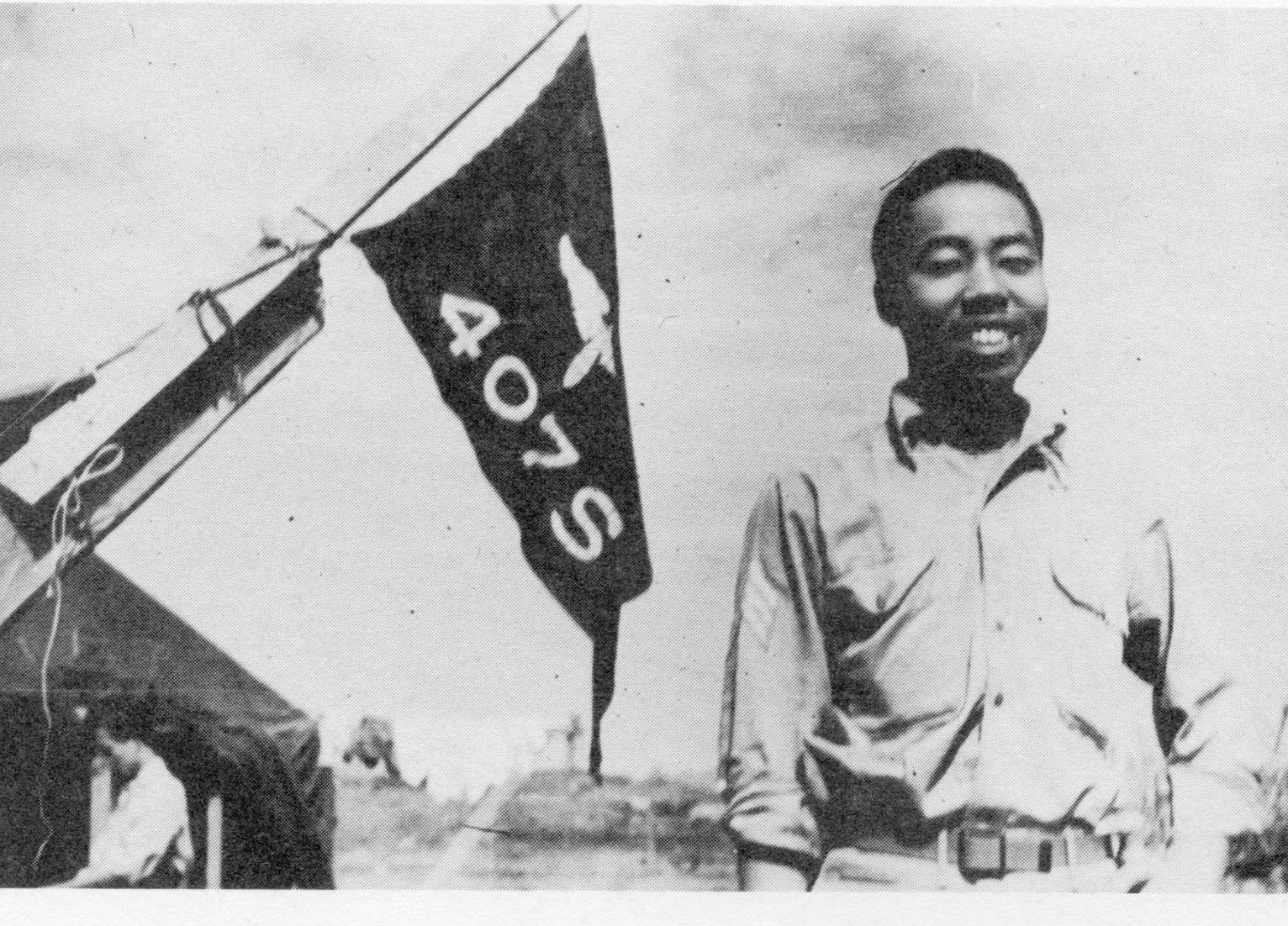

It's been all but forgotten that 20,000 Chinese Americans served in World War II. 61 percent of those who served were born in America, 39 percent from a foreign country. It is astonishing that in New York City alone, 40 percent of all Chinese Americans between 18 and 36 enlisted or were drafted -- the highest ratio among any national grouping in the country. Because some of the drafted and enlisted were "paper sons" who came to America with falsified papers, many of the men were actually younger or older than the legal age to serve. In one of the all-Chinese American units, the 407 Air Service Squadron, the actual age of the men ranged from 15-50.

Mack Pong pictured with Squadron flag at Chihkiang. Courtesy Albert Fong collection.

Eventually, Pong himself was drafted in 1943 and put in a unit of 250 Chinese Americans, which later formed the 407 Air Squadron Group of the 14th Air Service Group. They trained in Patterson Field, OH, and made their way to Calcutta. "Our group was formed, so we had to pick up supplies. Outside Calcutta was Kanchrapara, which was a service depot -- they had all the supplies. We had to pick up stoves for the kitchens, mechanical ware for the mechanics, food, practically everything to suffice, to make it self-serving. That was tough, because they had no cranes, and everything was transported by hand. Everything was moved onto a steamer ship on Brahmaputra River, then we had to take it off the boat, and put it on a narrow gauged railroad. Then we set up a base and squadron in operation at Dinjan."

After the war, the Chinese American soldiers promised to keep in touch and make something of their lives with their newfound rights. Over the years, Mack Pong kept in contact with at least 175 of the 250 Chinese American comrades, mostly those on the West Coast, from his 407 Air Service Squadron. Later, friends from the 987th Signal Company joined as well. Richard Chin of New York City, who passed away this year, kept in contact with those on the East Coast. Their initial reunions were informal dinners where the men drank and smoked cigars at the San Francisco VFW Hall. By the 60s, they brought their wives, and by the 80s, the reunions became family events.

Michael Williams and Lyn Johnson of the New York Veterans Administration, Minority Office, giving Mack Pong, with Christina Lim, a commendation for the reunion. Photo courtesy of David Len

Christina M. Lim is the daughter of Harry Lim, a veteran from the 407 Air Service Squadron. Along with her brother Sheldon Lim, she co-authored In the Shadow of the Tiger: The 407th Air Service Squadron, 14th Air Service Group, 14th Air Force, World War II and organizes these now yearly reunions. She explained how the World War II military service helped the Lim family get their first house in America. An army salary provided Chinese-Americans the basic, yet crucial step towards home ownership. "My grandma took the army pay that [her sons] sent home, and saved it. When they got out of the service, my dad came home and qualified for an FHA loan, and grandma used their army pay as a down payment on their very first house in America. My family went from renting flats and rooms to a nice three-bedroom house with a backyard. By then my grandfather was 86. He'd spent his whole life cooking for Caucasian families, as a house cook, and at last he could retire and prune the fruit trees in the backyard."

Richard Y. Wong, 89, of Hayward, California, was also in the 407 Air Squadron. He was able to bring a wife over from China easily, which, pre-war, was unheard of. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which allowed only 105 Chinese into America per year, was repealed in 1943. This was not done to pacify the Chinese Americans, but because it was considered distasteful to exclude people from an allied country. The War Brides Act passed in 1945 allowed American G.I.'s to marry and bring foreign wives to the U.S. However, Chinese War Brides entering the country were still charged to the 105 quota. Chinese American G.I.'s protested and on August 9, 1946, Congress passed the Chinese War Brides Act--which placed Chinese wives of American citizens on a non quota basis. The arrival of the thousands of Chinese brides transformed Chinatowns into family communities.

Richard Y. Wong was discharged in 1946. "There were many more [Chinese American] boys than girls. 5 boys to every 1 girl. In those days you could not date a girl. You had to have a mother or another older female relative go with you to meet her family. You couldn't just go with a father or uncle--who was working 12 hours a day anyway. My mother and aunts were stuck in China because of the quota. No mother here meant a girl's family wasn't going to accept you. In 1948 when I went back to China to get a bride, there were maybe 50 boys in the boat, like me, my age, looking for a wife. And I remember one guy got married within 10 days, because he had to come back for work. In my case, I stayed 6 months because my father had a place in Hong Kong. I came back 8 months later and had 3 kids."

Photos: Richard Y. Wong and Guy Yep in Assam, India, 1944. Courtesy Richard Y. Wong collection.

Richard Y.Wong, Guy Yep, Lily Yep, at American Legion Kimlau Post, New York, 2011

"I figured this might be the last one."

He wore a Bronze Star on his jacket awarded to him by the VA. In China, he was at the scene when an American plane carrying Chinese soldiers crashed. "I got five of them to the hospital. And the Americans couldn't take care of them. So they said, take them to a Chinese hospital. We took them to five different hospitals, and finally one of them said 'we'll take them.'"

Uniformed service is not often considered a major part of Chinese American life and culture today, yet through a decade of formative struggles in the 1940s, this World War II generation has achieved citizenship for themselves and their family members, transformed Chinatowns, and helped to establish the integrated landscape we know today.

Copyright © 2012 TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc.